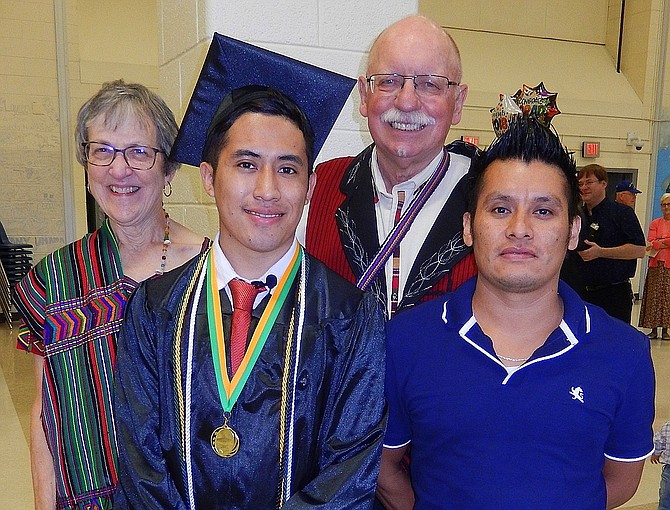

Brayan Brito’s June 2018 graduation from Mountain View: Friends Alice and Jerry Foltz with grad Brayan Perez Brito and his brother, Diego Chavez Brito. Photo by Bonnie Hobbs.

Today, Brayan Brito is a typical college student, busy with classes and exams, and with a bright future ahead of him. But his life wasn’t always so rosy.

He had a tough upbringing in his native Guatemala and hit rock bottom before deciding to come to the U.S. But that decision has made all the difference for him.

Raised by a single mom, Brito had three half-brothers and one younger brother. And his last two years there, ages 15 and 16, were particularly depressing.

“People hated me for being my father’s son because he had another family first, with seven children,” said Brito. “So I got bullied. Before I was born, he was in prison for eight years. And when he got out, he only took care of his first family. Then he went to the U.S. and came back when I was 16.”

“I cried when I saw him because I thought things would be amazing,” continued Brito. “But when I’d tell him my dreams, he’d say I’d never be better than him, and it made me feel so bad.” Meanwhile, the bullying continued, and someone threw a Molotov cocktail at his home.

By then, he considered killing himself and set fire to a pile of clothes in his bedroom, thinking he’d die of smoke inhalation while he slept. “But I woke up later with people around my bed,” he said. “My mom had seen the smoke and called family members and neighbors to come.”

“That’s when I knew I’d lost my sense of life and had to do something to make a change,” said Brito. “So I decided to go to the U.S. I only had a half hour before I had to leave, and I couldn’t even say goodbye to my little brother — and I love him. But I said goodbye to my mom, and she understood it was the best thing for me.”

Brito knew someone else who’d planned to leave the country, but couldn’t make it, so he took his place. His older brother Alex, 18, took him to a larger city to meet with a man who’d take Brayan and others to the Guatemalan/Mexican border

He’d had some money, clothes, good shoes and his cell phone with him. Then, while still in Guatemala, he left his backpack in a stranger’s car along the way and lost everything. “But Alex gave me the money he’d saved for college and his favorite, strong shoes, in exchange for the poor ones I was wearing,” said Brito. “Then Alex returned home and eventually attended and finished college.”

It took about 45 days to get to the border, traveling by taxis, cars, buses and on foot. “At one point, I stayed in a house in Mexico with 19 people,” said Brito. “Then it took about a month to reach Texas.”

It was 2014, and he was coming to Centreville to live with his half-brother who’d already been here 10 years. “It took a long time to get here because I kept getting separated from my traveling group,” said Brito. “I got lost, and a wonderful, American family in Texas helped me. I rejoined the group, then got lost again in the desert, but found the group again.”

After two more days, around 2 a.m., they were surrounded by immigration agents. “We just gave up,” said Brito. “But I didn’t want to go back to Guatemala, so I slid down a hill of sand and ran from tree to tree until I got out of the area. One of the agents got close and asked me in Spanish, ‘Are you sure you want to do this? Do you have enough water?’ But I didn’t think about the danger – I just wanted to escape.”

Once he did, he fell asleep in some tall grass. “When I woke up, there was just sand and emptiness everywhere,” said Brito. “I only had one bottle of water, a can of juice and some almonds for three-and-a-half days, alone in the desert.”

He walked in the direction his group had been traveling before. “I was afraid immigration would find me; so in open areas, I’d run, instead of saving energy,” he said. “I conserved water, too, and only drank a few drops at a time — and it tasted delicious.”

At night, Brito heard animals, including coyotes, all around him. But he said he felt at peace and wasn’t afraid of them. Eventually, he saw a tiny light, far in the distance, so he walked toward it. It took one-and-a-half hours to get there and it was a military base, but he walked past it and ended up on a deserted highway, walking almost five more hours before he was picked up by immigration.

He was arrested and placed in a camp with other minors for 28 days. But unlike in similar camps today, Brito said he and the others were treated well, fed and given school classes. “It was a good place and less dangerous than home was,” he said. “I had a court hearing, and they eventually released me to my brother.”

After a couple weeks, though, he became homeless. Yet once he started school at Mountain View High, things started looking up for him. Although – like everything else in his young life then – it wasn’t easy.

“I rented a couch in someone’s house for $150/month,” said Brito. “I worked as a busboy in a Korean restaurant, six days a week, 12 hours a day. I attended school from 8 a.m.-2:50 p.m. and had just 10 minutes to get to the restaurant by 3 p.m. I worked until 3 a.m. and was very tired. I walked back and forth from where I lived and only got three or four hours of sleep.”

Luckily, he said, Mountain View doesn’t give homework, so he did all his schoolwork in class. “I was in survival mode, but was inspired,” said Brito. “I fell in love with science when I saw documentaries about quantum mechanics, astronomy and famous scientists. And although I couldn’t understand it all, I began listening to their stories with a wireless earbud while I worked.”

But speaking English was another matter. “When I arrived I Centreville, I spoke no English,” said Brito. “After one-and-a-half years, I knew enough to comprehend things and interact in society. And after three years, I became fluent and it became my language.”

However, he said, “I was still full of hate because my family didn’t take care of me and I wanted to prove my father wrong. He told me I wouldn’t be anything, and I said, ‘Come find me in 10 years.’” And he credits Mountain View, its teachers and counselors with giving him the tools he needed for success.

When Brito first went there, all he could say in English was, “Does anyone here speak Spanish?” Fortunately, his counselor, Tina Perez, and several other staff members did. They told him about this school of second chances guided by the motto, “Family, Love and Respect,” and said he could graduate in four years.

“I was happy,” he said. “They welcomed me and made me feel like home. Going there every morning was a feeling of having fun and being with friends. The teachers believed in me, and I focused on work and studying. All the teachers became my friends.”

Brito, a lawful permanent resident as a Green Card holder, began working at the Centreville Immigration Forum and became a volunteer director, using his talents to help others. And he participated in GMU’s Dream-Catchers program, which mentor students needing help overcoming their obstacles to getting an education.

He eventually became an excellent student who was honored with awards and several scholarships from Mountain View. In addition, he received the 10th Congressional District’s highly competitive Harry F. Byrd Jr. Leadership Scholarship and a check for $10,000.

But that’s not all. One of the panel members who interviewed Brito for that scholarship was Shenandoah University President Tracy Fitzsimmons. And she was so impressed by his story that she offered him a Presidential Scholarship of $20,000 a year for four years — a possible total of $80,000.

He started there in August 2018, majoring in math and hoping to someday obtain a Ph.D. in mechanical engineering and, possibly, business. “I eventually want to own my own business,” said Brito. “I hope to combine the logic of math with mechanical engineering to design things, and with business to make a profit out of my own inventions.”

In his 30s, he said, he might join the Air Force and possibly do a project with NASA. In his 40s, said Brito, he might go into politics “to help people.” So what advice would he give to others struggling to succeed? “In anything you do, just start it,” he said. “Get into it as deep as you can, and everything else will fall into place.”